Photo: Roma Flowers

By Andrew Sharp

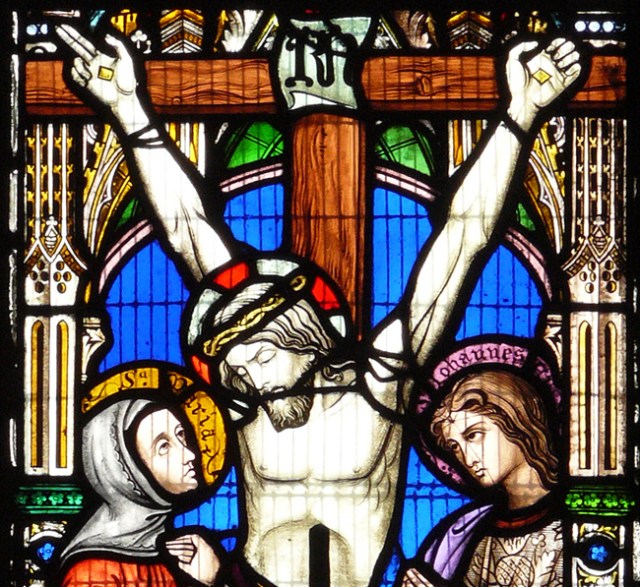

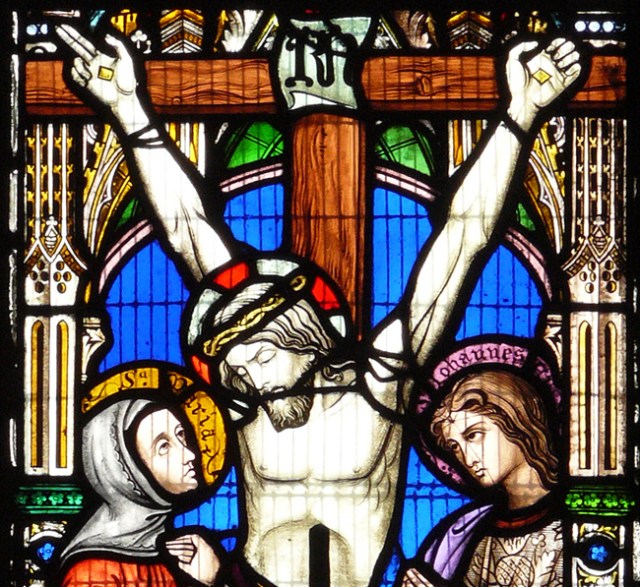

The old man stood with his back to a congregation of empty pews, looking up at the outstretched arms of a wooden crucifix that towered over him. Rows of candles lined an altar nearby, but their dead wicks added no light or heat to the drafty shadows. The man’s lips moved as he looked up at the crucifix, but the crucifix gazed away in agony toward the dark ceiling beams, consumed with its own worries. The old man did not turn when the doors to the sanctuary creaked open behind him and footsteps came down the aisle.

“Father James?” a voice said with a trace of a Spanish accent.

Father James Butler turned then and smiled politely. “Father Almeda,” he said quietly to the young man standing there. “Martin, if I may. How are you settling in at the presbytery?”

“It is very comfortable, thank you,” the young priest said. “Although that is not important.”

“I know,” Father James said. “I just get used to asking, after all this time. It seems natural. What can I do for you?”

“We have things we need to discuss,” Martin said. “They are not happy, you know.”

Father James stood with his arms crossed looking up at the crucifix again. “I know,” he finally said. “That’s why you’re here.”

“Yes,” Martin said. “But there is no need for concern. They sent me to help you.”

“Because I’m growing old and frail?” Father James asked with more sarcasm than is proper for a priest.

“Because you have deviated from your purpose. I am here to help you back to that purpose, if you are willing. You still have much service to render.”

“You’re new. You don’t understand yet,” the old man said. “But you will find out that the service they require has its flaws.”

Martin frowned.

“And you’re made in the image of God, like I am,” Father James continued. “Too much in his image. Death doesn’t come naturally. It’s a terrifying thing, losing life, once you have it. But death is built into you too. You have to face it someday. And you will understand then.”

“We aren’t made to worry about those things,” Martin said, looking at the old man as if he had suggested that catching a cold was an injustice. “Faithful service …”

“Comes to an end,” Father James said. “And then what?”

“It does not matter!”

“It does to me.”

“I cannot force you to give up these heresies,” Martin said. “But it would be much better for you if you did. It is best that I am here now. Your condition is worse than I thought.”

“And what if I don’t repent?” Father James asked.

“I urge you not to pursue that course,” Martin said, his voice chilly as the empty room.

Father James sighed. “It might be too late for me.”

Sixty years ago, when the new priest had braked for the third red light on the way into Wootensburg, Ohio, across from Smith’s Old Fashioned Drug Store, it struck him that he had drawn an easy assignment. The group he had studied with had been trained to handle the challenges of any metropolis in the world. Seven minutes after reaching the town limits, Father James was sitting in the downtown district of Wootensburg. This would be easy.

Wootensburg was small, but it wasn’t run down. It was built where the Appalachian foothills finally melted down into flat Midwestern farm land, but the resignation and aimlessness that oozed out of the impoverished mountains into so many small towns had not reached Wootensburg.

The downtown district had, among other establishments, several antique shops, two restaurants (Betty Jo’s Home Style Restaurant and the Country Buffet), a McDonald’s, the offices of the Wootensburg Herald-Press, a sporting goods store, and the pub. These little economic engines rarely ran at high speed, but like an old well-tended diesel, they kept reliably putting along. Mostly, anyway. The town’s coffee shop reopened every six months or so under new, and temporarily optimistic, ownership. The stores were doing good business on this evening. As the sun eased down behind the courthouse, the still-warm sidewalks were busy with retired people, workers getting off for the day, and families out for a stroll.

Not far off Main Street the stone towers of Our Lady of Peace Catholic Church, the priest’s destination, stood out high above the surrounding buildings.

He pulled his car into the driveway of the presbytery, a little stone house that was dwarfed by the church next door. A porch ran across the front, with a rocking chair by the door. The young priest reflected that he would be far too busy getting the parish in shape to use the rocking chair.

It wasn’t that the priest thought the town would turn out to be a sinkhole of evil. He liked the looks of it so far. But he carried the church’s doctrines with fervor, and bore the clergyman’s conviction that society was crumbling heedlessly into decay and needed to be built up again by some thoughtful person. His overseers, sharing his convictions, had sent him here to do just that.

They trusted his ability more than they usually did with new young men of the cloth. If their calculations were correct, Father James would be up to any challenge, immediately. And he would not be warped by the pressures of his job. He was a product of a new, extremely expensive program. It was designed to use advanced technology to ensure perfectly reliable clergy, a commodity that was increasingly in short supply. Wootensburg was a safe place for a trial run.

The reliable little town gave Father James a warm, if appraising, welcome. The newspaper editor wrote a nice editorial about the new leader at Our Lady, in which he hoped, in optimistic first person plural, that the new priest would understand the town’s needs and put his (approvingly noted) theological credentials to work for the public good. The church’s ladies group threw a welcoming supper.

Eyes in the parish also watched Father James carefully to see what kind of priest he would turn out to be. Would he be down-to-earth, genial about small flaws like a little overindulgence in alcohol now and then, or a missed Mass here and there, or would he be alarmed by such lapses? Would he content himself with enlightening homilies, or interest himself too much in how the flock applied them?

Father James turned out to be difficult to judge. He was unwaveringly kind and warm, interested in the parish families, and though very scholarly he clearly understood practical everyday matters. Gradually, though, the flock discovered that their new shepherd, despite his kindness, had an iron side and an uncomfortable tendency to prod them toward righteousness. One saved the good jokes until later when Father James was around. He had no endearing faults. He did not eat too much. He excercised enough. He was on time. He got up early in the morning, worked hard, kept his word, told the truth, and in general was uncannily good.

“He’s a pretty nice guy,” Hector the local plumber, a church member, gloomily summed up one evening for a few others who were gathered at the pub engaging in their every-now-and-then overindulgence, “but you don’t feel like you can relax around him.”

There was a silence.

“Nice, though,” Hector repeated, as if troubled that he did not believe himself.

Father James was not only objectionably good, but he was not shy about speaking out when it was clear that a good orthodox opinion was lacking in the public debate. Some in the town resented what they called his pushiness on social issues. A good many just ignored the priest. A sizable number of the town were stout Baptists or members of the scattered nondenominational Houses of Praise or Fundamental Bible Churches. They viewed Catholics as one step better than pagan, and weren’t sure if they didn’t prefer the pagan.

Our Lady of Peace did not fill up with new members in the following years, although a number were added through reproductive means. The seeming stagnancy did not dampen Father James’ zeal, or his confidence. His happiness was seemingly unaffected by his circumstances. He counseled, he preached, he cheerfully ushered the members of the little town in and out of life. Whether they approved of him and wanted to invite him over for beer on Saturday evenings was not his problem.

He was not aware of the arguments and grumbling conversations going on in the offices of his overseers. They had expected more return on their steep investment.

“He’s giving us no trouble,” his defenders said. “There’s no corruption. And he runs things flawlessly. You can’t change the world in five years, or even a decade.” His detractors grudgingly admitted the truth in this. Father James did not appear in the newspaper at unscheduled times, and this alone was worth quite a bit of the money they had paid.

Those in the parish who had their differences of opinion with church authority were even less enthusiastic about him.

“You have no compassion,” Sister Watts, the head nun at the local convent, told him one afternoon, with her arms crossed. The convent had an unsavory reputation higher up in the church hierarchy because the nuns often ignored the gentle guidance of said hierarchy. This might have been overlooked as a byproduct of strong leadership, but they were of a gender that was not supposed to dissent. Part of Father James’ job was to keep an eye on the nuns and remind them of the will of the bishops.

What had provoked Sister Watts’ arm-crossing in this case was Father James remonstrating with her about the nuns’ vocal opposition to political policies they deemed harsh toward the poor. They had even gone so far as to march around with signs, a dangerous indicator of moral unsoundness.

“I have plenty of compassion,” Father James told her firmly. “I just don’t trust my own judgement in everything, as you seem to do. I give authority its due respect. And so should you. You’d have a lot more peace.”

The nun, not being perfect like Father James, remained irritated. “And what happens when authority is wrong?” she demanded. “You ought to question authority, not just follow it around blindly.”

“They will answer to God, not me, if they are wrong,” he told Sister Watts gently, in a soothing tone. Sister Watts was considerably unsoothed.

“Yours not to reason why? Yours but to do or die?” she asked sarcastically.

“Nobody’s getting killed,” he said. “We’re talking about the bishops not wanting you marching around on the street shouting and waving signs. But yes, if it came to that. Mine but to do or die.”

“Like a robot,” she snapped.

“No,” he said.

“Like a sheep.”

“We are to follow the Shepherd,” he said. “Yes. Like a sheep. It would behoove you and the sisters,” he said, “to model yourselves a touch more after sheep. Right now you seem to be getting your inspiration from … other animals.”

The nun was able to restrain herself from kicking the priest in the groin, a feat she later marveled about. Altogether, she felt her restraint ought to count for quite a bit of purgatory served. Instead of kicking, she said with passion, “And what if God is not on authority’s side? Those holy authorities are great at standing up for church tradition, but sometimes they completely miss God’s compassion for the powerless. And ‘If a blind man leads a blind man, they will both fall into a pit.’”

Father James was not troubled by her scripture quoting. “Obey your leaders and submit to them; for they are keeping watch over your souls,” he shot back. “Unlike you, Sister Watts, I am willing to give authority the benefit of the doubt.”

Although he showed no doubt, either then or in the years that followed, the nun’s words stuck with him, and ate away at his peaceful confidence. The priest had expected his biggest tests to come at times of momentous crisis. But it turned out to be the small, unexpected moments like his confrontation with Sister Watts that caught him off guard and eventually derailed him.

Another of these small moments came after several decades on the job. Father James had just led a funeral service for a local farmer, a grouchy, stingy man who had not been much of a churchgoer. He had died suddenly at age 55. The man’s teenage daughter, a conscientious church member, was crying afterward as she left and Father James paused to offer some sage words of consolation.

She ignored these, and blurted out at the startled priest, “Do you think he made it to heaven?”

Father James took a deep breath. Clergy dislike this question, and to his shock he found that his prepared answers did not answer the question to his satisfaction at all. This had not happened before. He mumbled something about God being just and fair, so we can trust him to do what’s right.

She seemed to wilt. “That’s easy for you to say,” she said in a flat voice. “You always do everything right. You know you’re going to heaven when you die.”

He stood there silent. Heaven. When I die.

From that moment, to his gnawing doubt he added dread. Both started small and grew slowly, but they were there to stay.

He took to sitting out on the front porch in his rocking chair in the evenings, rocking in an anxious, steady rhythm as if he were trying to escape on it. He would watch the sun set behind the houses across the street, and the red light change on Vine and Cross streets, the cars flowing by. Sometimes the people in them waved. Young people and families walked by. In the summer many of them would be holding ice cream cones and milkshakes from the ice cream stand up the street. He wanted to be like them. He wanted the comforting faith that so many of them ignored. Instead, he just rocked his chair, for hours.

On one of these evenings, a number of years after he had arrived in town, Father James was sitting in his rocking chair, going over his homily as darkness settled on the street. It was one of the lifetime’s worth of approved meditations his superiors had given him to deliver. But the words stood out to him differently this time.

“If I have prophetic powers, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but have not love, I am nothing.”

He rocked viciously for a while, musing on societal decay, rebellious nuns, dead farmers and their daughters, and answers he no longer trusted.

“I’m worried about you,” Roy, Father James’ atheist friend, told him. They had become friends not long after the priest came to town, and over the years had often enjoyed sparring over philosophy. “It’s no fun arguing with you any more. Sometimes you look like you believe what I’m saying.”

“Oh, no, it’s not that,” the priest reassured him. “It’s that I don’t always believe myself.” He stared at his reflection in his coffee and then sloshed it around.

“Come again?” Roy asked. “You don’t believe me, you don’t believe yourself. What other options are there? You’re not becoming a Buddhist, are you?”

“No,” Father James said. “No, I believe in the gospel more than I ever have. I’m just not sure I’m teaching it.”

“Going to nail up some theses, eh?”

“NO,” Father James said. “That’s not what I mean. I’m supposed to be perfect. And I’m not. My creed is supposed to be perfect. And it isn’t.”

“That’s very humble of you,” Roy said.

Father James did not seem to hear him. “And the worst thing is, I’m like the man selling movie tickets. The show isn’t for me.”

“You’re not making any sense,” Roy said.

The priest looked the atheist in the eyes. “Roy,” he said slowly. “I have no hope.”

The parish watched Father James change, although they had a hard time saying what was different. He fulfilled all his duties and for a while, he delivered perfectly orthodox sermons, the same as ever. But he seemed to shrink, and his eyes were sad.

Eventually, he changed too much. He deviated from his lines. He questioned things publicly. His overseers might have tolerated this in others, but they had invested too much money and time to overlook it in Father James. They warned him. Several times. Father James did not listen.

This was unwise, because the authorities were perfectly aware of everything he did. Tense conversations took place at very high levels.

“The thing is,” the bishop in charge of the new program told an Italian cardinal, “we were told this was not supposed to happen. The technology is supposed to be fail-proof.”

“Yes, we were told that, weren’t we?” the cardinal snapped. “But I was always afraid that was too optimistic. We’ll have to go to the emergency plan.”

Martin shook the priest’s shoulder. “Once again, I tell you Father James, we are not to question these things. We are here to serve. Leave your worries to those you serve. They have your best in mind.”

Father James smiled bitterly. “Whom do I serve? God? The church?”

Martin didn’t answer.

“You talk of serving. Who are you serving?” Father James pressed. “The church or God?”

“There is no difference,” Martin said coldly. “And if there is, it doesn’t matter to me. I am done arguing with you about it. Are you going to repent and recommit to the service you are called to or are you going to continue with this rebellion? I give you fair warning — they have no use for you if you persist on the course you have chosen.”

Father James looked wistful. “Repent, you say. I wish I could.”

He slowly turned and knelt under the crucifix.

Martin grabbed the old man’s robe and tore it open down the back. He pressed Father James’ spine with a series of swift motions and a panel swung open, appearing seemingly from nowhere out of the old priest’s sagging skin. Inside was a maze of wires and circuits.

Father James flinched, but he did not struggle. He raised his hands and looked toward the ceiling. “Father, into your hands I commit …” and then he stopped. He made a sound like a sob, or a gag.

Martin pulled a small taser out of his pocket and stuck it into the open panel. He pulled the trigger. There was a violent flashing and popping.

Father James’ eyes went blank, and he slumped down onto the floor. Martin closed the panel and gently laid the old man on his back. His face was empty, and a small wisp of smoke trailed out of his nose.

Martin stood looking down at him for a minute. Then he ran to the door and looked out at the dark street. It was empty. He came back and gathered up the body. They would find the old priest in his bed, where he had died peacefully in his sleep.

The church would handle all arrangements.